Flipping Through Fluent Python: The First Example

Today, in a fine November afternoon, I was flipping through the book — Fluent Python. Though I should not say "flipping," because I stumbled upon the very first example.

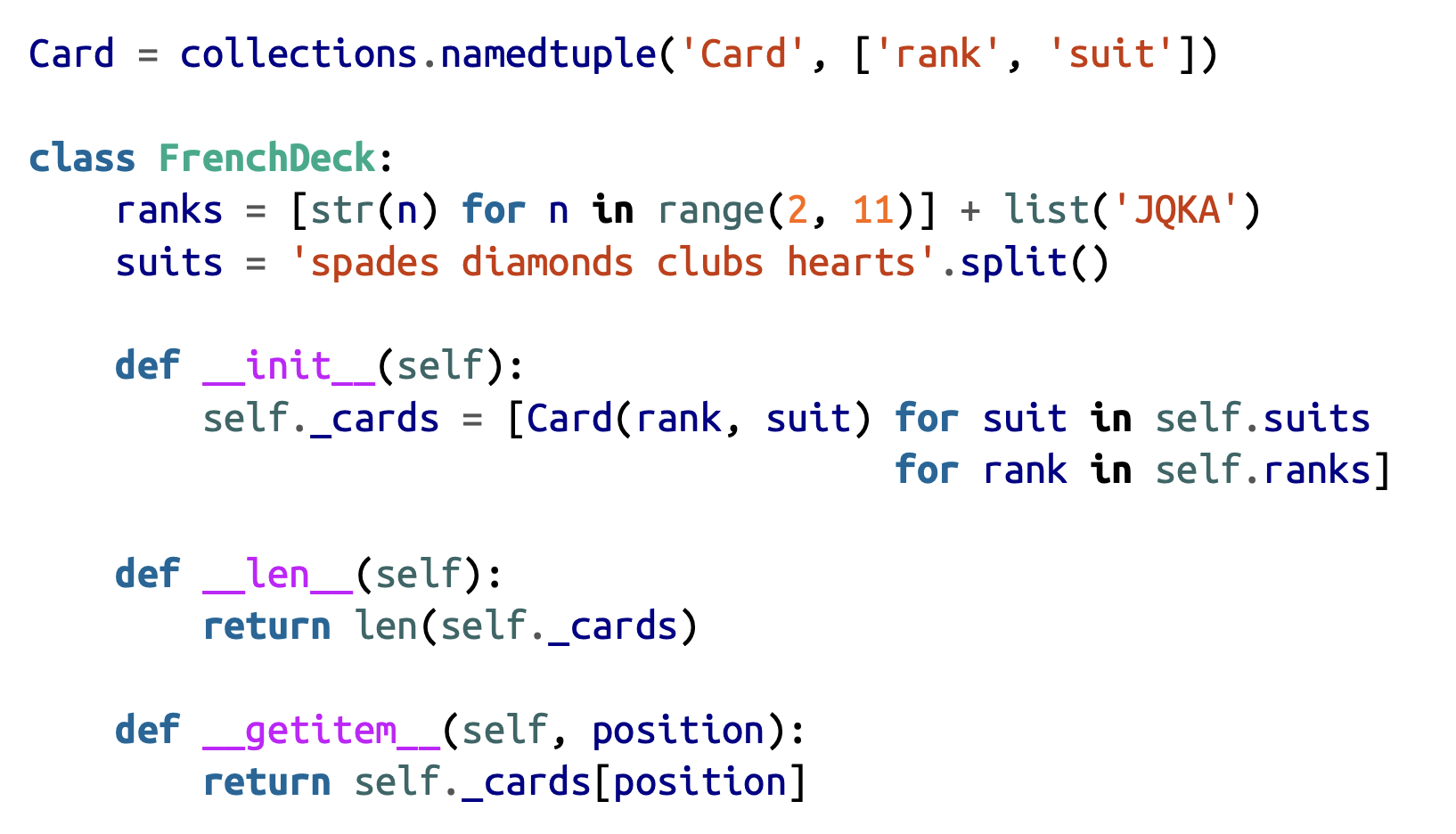

import collections

Card = collections.namedtuple('Card', ['rank', 'suit'])I was wondering — wtf is this Card doing? Is this creating a class? Or an object? Or what?

Turned out, namedtuple is a factory function. "Factory function" was a new (still fresh) term to me. It sounded fancy, but I interpreted it like this: it’s a function that makes a class for me. So Card is now a class, and when I do Card('A', 'spades'), I get an instance of it. Each card is immutable, lightweight (compared to a full custom class, namedtuple creates a very small, memory-efficient object; it doesn’t have a __dict__ for storing attributes dynamically, which saves memory and is faster to create), and has fields accessible by name, which improves readability and reduces errors. For example, c.rank and c.suit clearly indicate what data they hold, enhancing clarity and maintainability.

Reviewed the underscore conventions, just a footnote — a single leading underscore (_attr) signals internal use, a double leading underscore (__attr) triggers name mangling to avoid subclass conflicts, and a trailing underscore (attr_) is used to avoid naming conflicts with Python keywords. _cards follows the first convention: it holds all the card objects, but the class doesn't expose the list directly, instead providing a controlled interface through Python's special methods.

By implementing __len__ and __getitem__, the deck behaves like a standard Python sequence (i.e., an object that supports indexing, slicing, iteration, and len() just like a list, tuple, or string):

def __len__(self):

return len(self._cards)

def __getitem__(self, position):

return self._cards[position]__len__ allows len(deck) to return the number of cards. __getitem__ allows indexing and slicing: deck[0] returns the first card, deck[:3] returns the top three, and deck[12::13] selects all the aces. Because _cards is a list, these operations are handled automatically, and the deck also becomes iterable. I can loop over it, pass it to random.choice, or slice it any way I like — all without writing extra code.

The combination of namedtuple for cards and the sequence protocol for the deck shows the coolness of Python's data model: minimal, clear, and fully integrated with built-in operations.